Lasers vs. Sledgehammers: Why the Most Complex Devices in Technology History May Be Sanction-Proof

China’s booming semiconductor imports reveal a stark truth: sanctions might be the blunt sledgehammer against a market thriving on precision and complexity. As the U.S. contemplates stricter trade restrictions, can this strategy contain a tech arms race, or will it spark a new era of covert technological warfare?

Advanced Semiconductor Technology: Weapon or Battlefield?

The power of advanced semiconductors, as we have outlined in previous articles, has given birth to whole new industries from real-time surveillance, large scale data analysis, AI and advanced modeling with more to come. The semiconductors of today are product, commodity, and critical R&D tool all at the same time. This unprecedented triangulation has created prosperity and competition, along with political tension as nations are tempted to acquire capabilities through geopolitical or even military means.

The Biden administration is considering the strictest trade restrictions yet to limit China’s access to advanced chip-making machines. Despite escalating U.S. sanctions, Japanese and Dutch companies, Tokyo Electron and ASML, continue supplying these critical machines to China. This tension might explain the recent 7% drop in Nvidia shares and forecasts of further declines. Are we entering a semiconductor arms race that could undermine global free trade? Can the blunt instrument of sanctions, imperfect but effective for oil and nukes, work to control tensions over devices that can be hidden in a pair of socks and are manufactured by machines that make Swiss watches look like dishwashers from the 1950s?

Ineffectiveness of Current Sanctions

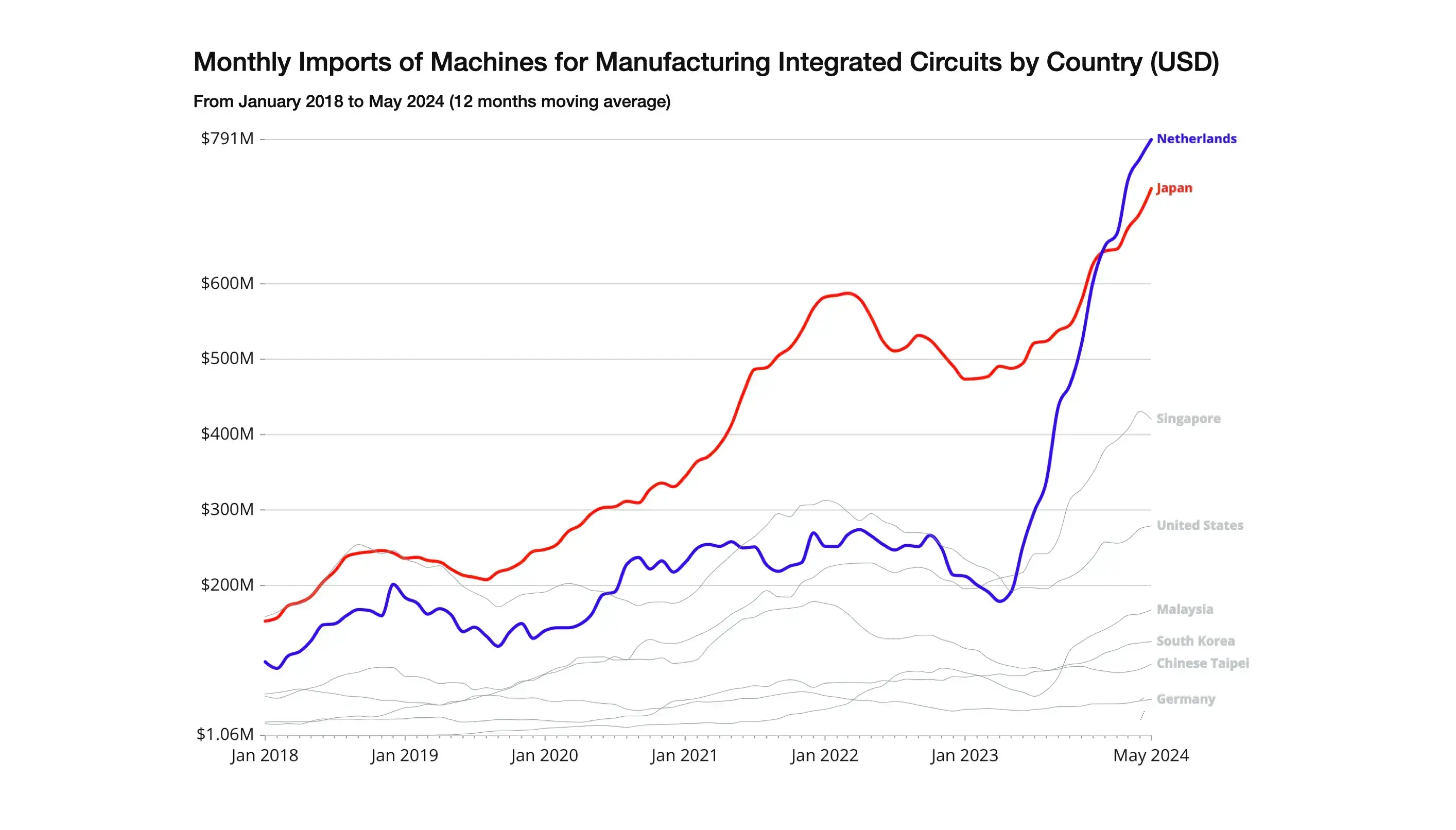

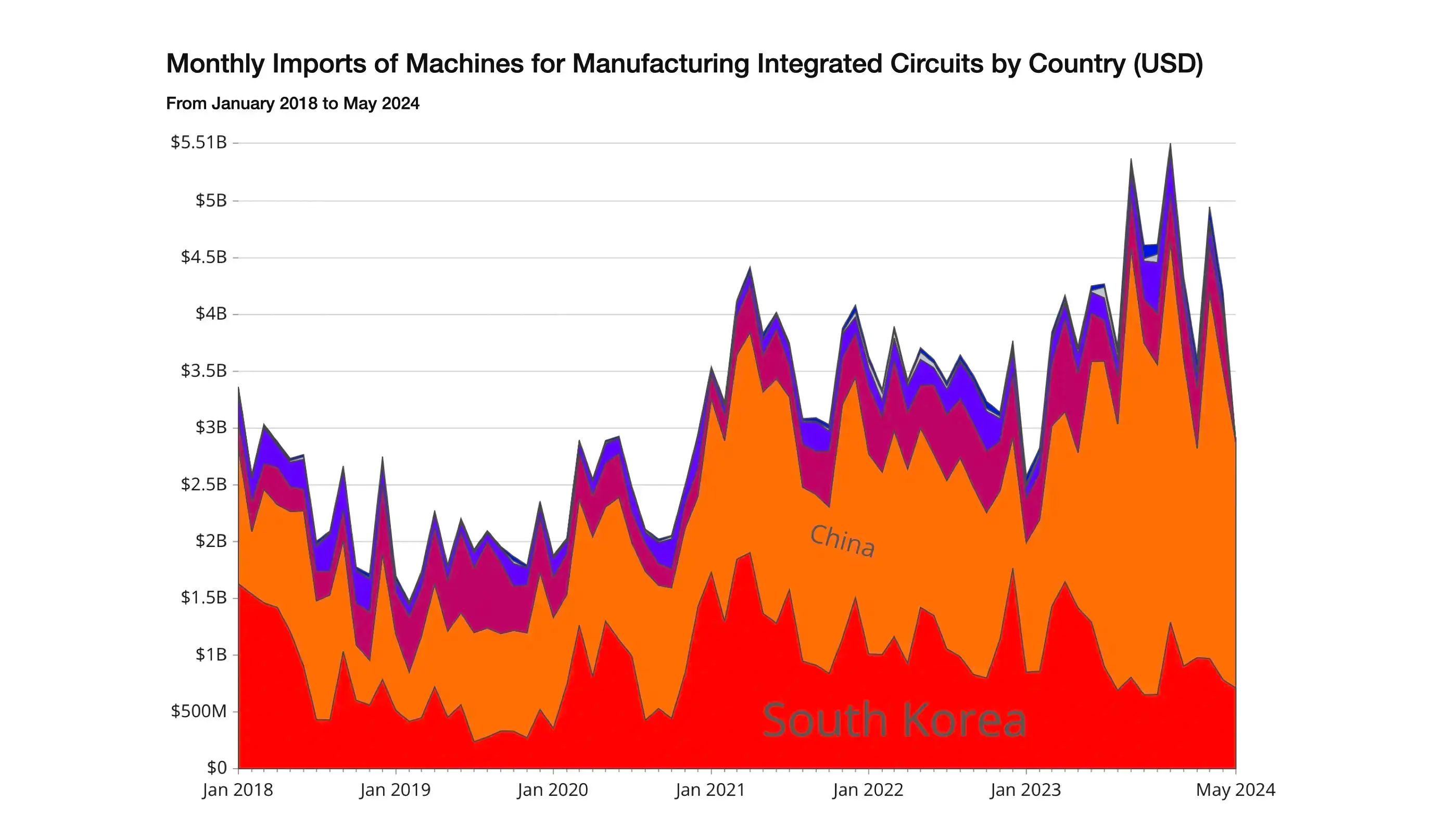

Despite U.S. efforts to restrict ASML’s sales to China, the impact has been limited. In May 2024, China’s imports of chip-making machines reached $2.17 billion, a 58.4% increase from the previous year. Imports from the Netherlands grew by 78.3% to $684 million, with nearly half consisting of machines for electronic circuit manufacturing. In Q2 2024, nearly half of ASML’s €6.9 billion revenue came from the Chinese market, with exports increasing by 40% year-over-year. Similarly, imports from Japan, home to Tokyo Electron, surged to $711 million, up 120%, with China accounting for 26% of Tokyo Electron’s total revenue. So much for the current round of sanctions.

Genii out of the Bottle… or is there even a Bottle Anymore?

The Biden administration is contemplating invoking the foreign direct product rule, targeting Tokyo Electron and ASML, which rely on U.S. technology for manufacturing. This could significantly disrupt their operations, as seen in their stock plunges in July. In 2023, China accounted for 70% of global imports of machines for making electronic integrated circuits, totaling $27.4 billion. How can sanctions be designed without crippling the entire industry or pushing it underground?

Stricter U.S. trade restrictions could strain relations with allies, particularly Japan and the Netherlands. Analysts foresee a global market response, with India and Southeast Asia emerging as alternative semiconductor hubs. India, with its growing tech industry and initiatives like “Make in India,” aims to reduce dependence on imports and boost local production. Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore also offer favorable environments for semiconductor manufacturing, investing in infrastructure and workforce development.

Facing the China-saurus: Big, Strong and no Fossil Regarding “Techspertice”

Substantial investments in research and development, coupled with a strategic focus on technological independence is China’s most powerful hand to play to fight the impact of sanctions.

China’s response to previous restrictions has been to bolster its domestic semiconductor industry through initiatives like “Made in China 2025.” China has the cash and infrastructure to quickly create homegrown semiconductor capabilities. Partnerships with non-U.S. companies and countries less aligned with U.S. policies provide alternative avenues for acquiring necessary technologies and expertise.

Given China’s vast market size and economic influence, completely isolating it from advanced semiconductor technologies is probably a fool’s errand.

Conclusion

The Biden administration’s consideration of stricter trade restrictions on China may be on hold in the current US election turmoil but a reckoning in the advanced semiconductor space is coming. Whether we are talking about Beijing/Taiwan, US investments in domestic advanced manufacturing, or an attempt to initiate a Semiconductor Cold War to control the proliferation of technology, the world is being tested. Can some form of world governance do a better job of regulating the alarming capabilities of AI and advanced semiconductors than the United Nations has done with war prevention and nuclear proliferation? It’s clear that this issue will dominate the coming decades and it is not just about China.